- CLASSIC MAGAZINES

- REVIEW CREW

A show recapping what critics thought back

when classic games first came out! - NEXT GENERATION'S BEST & WORST

From the worst 1-star reviews to the best

5-stars can offer, this is Next Generation! - NINTENDO POWER (ARCHIVE)

Experience a variety of shows looking at the

often baffling history of Nintendo Power! - MAGAZINE RETROSPECTIVE

We're looking at the absolutely true history of

some of the most iconic game magazines ever! - SUPER PLAY'S TOP 600

The longest and most ambitious Super NES

countdown on the internet! - THEY SAID WHAT?

Debunking predictions and gossip found

in classic video game magazines! - NEXT GENERATION UNCOVERED

Cyril is back in this spin-off series, featuring the

cover critic review the art of Next Generation! - HARDCORE GAMER MAGAZING (PDF ISSUES)

Download all 36 issues of Hardcore Gamer

Magazine and relive the fun in PDF form!

- REVIEW CREW

- ELECTRONIC GAMING MONTHLY

- ELECTRONIC GAMING MONTHLY RANKS

From Mario to Sonic to Street Fighter, EGM

ranks classic game franchises and consoles! - ELECTRONIC GAMING MONTHLY BEST & WORST

Counting down EGM’s best and worst reviews

going year by year, from 1989 – 2009! - ELECTRONIC GAMING BEST & WORST AWARDS

11-part video series chronicling the ups and

downs of EGM’s Best & Worst Awards!

- ELECTRONIC GAMING MONTHLY RANKS

- GAME HISTORY

- GAME OVER: STORY BREAKDOWNS

Long-running series breaking down game

stories and analyzing their endings! - A BRIEF HISTORY OF GAMING w/ [NAME HERE]

Real history presented in a fun and pithy

format from a variety of game historians! - THE BLACK SHEEP

A series looking back at the black sheep

entries in popular game franchises! - INSTANT EXPERT

Everything you could possibly want to know

about a wide variety of gaming topics! - FREEZE FRAME

When something familiar happens in the games

industry, we're there to take a picture! - I'VE GOT YOUR NUMBER

Learn real video game history through a series

of number-themed episodes, starting at zero! - GREAT MOMENTS IN BAD ACTING

A joyous celebration of some of gaming's

absolute worst voice acting!

- GAME OVER: STORY BREAKDOWNS

- POPULAR SHOWS

- DG NEWS w/ LORNE RISELEY

Newsman Lorne Riseley hosts a regular

series looking at the hottest gaming news! - REVIEW REWIND

Cyril replays a game he reviewed 10+ years

ago to see if he got it right or wrong! - ON-RUNNING FEUDS

Defunct Games' longest-running show, with

editorials, observations and other fun oddities! - DEFUNCT GAMES QUIZ (ARCHIVE)

From online quizzes to game shows, we're

putting your video game knowledge to the test!- QUIZ: ONLINE PASS

Take a weekly quiz to see how well you know

the news and current gaming events! - QUIZ: KNOW THE GAME

One-on-one quiz show where contestants

find out if they actually know classic games! - QUIZ: THE LEADERBOARD

Can you guess the game based on the classic

review? Find out with The Leaderboard!

- QUIZ: ONLINE PASS

- DEFUNCT GAMES VS.

Cyril and the Defunct Games staff isn't afraid

to choose their favorite games and more! - CYRIL READS WORLDS OF POWER

Defunct Games recreates classic game

novelizations through the audio book format!

- DG NEWS w/ LORNE RISELEY

- COMEDY

- GAME EXPECTANCY

How long will your favorite hero live? We crunch

the numbers in this series about dying! - VIDEO GAME ADVICE

Famous game characters answer real personal

advice questions with a humorous slant! - FAKE GAMES: GUERILLA SCRAPBOOK

A long-running series about fake games and

the people who love them (covers included)! - WORST GAME EVER

A contest that attempts to create the worst

video game ever made, complete with covers! - LEVEL 1 STORIES

Literature based on the first stages of some

of your favorite classic video games! - THE COVER CRITIC

One of Defunct Games' earliest shows, Cover

Critic digs up some of the worst box art ever! - COMMERCIAL BREAK

Take a trip through some of the best and

worst video game advertisements of all time! - COMIC BOOK MODS

You've never seen comics like this before.

A curious mix of rewritten video game comics!

- GAME EXPECTANCY

- SERIES ARCHIVE

- NINTENDO SWITCH ONLINE ARCHIVE

A regularly-updated list of every Nintendo

Switch Online release, plus links to review! - PLAYSTATION PLUS CLASSIC ARCHIVE

A comprehensive list of every PlayStation

Plus classic release, including links! - RETRO-BIT PUBLISHING ARCHIVE

A regularly-updated list of every Retro-Bit

game released! - REVIEW MARATHONS w/ ADAM WALLACE

Join critic Adam Wallace as he takes us on a

classic review marathon with different themes!- DEFUNCT GAMES GOLF CLUB

Adam Wallace takes to the links to slice his way

through 72 classic golf game reviews! - 007 IN PIXELS

Adam Wallace takes on the world's greatest spy

as he reviews 15 weeks of James Bond games! - A SALUTE TO VAMPIRES

Adam Wallace is sinking his teeth into a series

covering Castlevania, BloodRayne and more! - CAPCOM'S CURSE

Adam Wallace is celebrating 13 days of Halloween

with a line-up of Capcom's scariest games! - THE FALL OF SUPERMAN

Adam Wallace is a man of steel for playing

some of the absolute worst Superman games! - THE 31 GAMES OF HALLOWEEN

Adam Wallace spends every day of October afraid

as he reviews some of the scariest games ever! - 12 WEEKS OF STAR TREK

Adam Wallace boldly goes where no critic has

gone before in this Star Trek marathon!

- DEFUNCT GAMES GOLF CLUB

- DAYS OF CHRISTMAS (ARCHIVE)

Annual holiday series with themed-episodes

that date all the way back to 2001!- 2015: 30 Ridiculous Retro Rumors

- 2014: 29 Magazines of Christmas

- 2013: 29 Questionable Power-Ups of Christmas

- 2012: 34 Theme Songs of Christmas

- 2011: 32 Game Endings of Christmas

- 2010: 31 Bonus Levels of Christmas

- 2009: 30 Genres of Christmas

- 2008: 29 Controls of Christmas

- 2007: 34 Cliches of Christmas

- 2006: 33 Consoles of Christmas

- 2005: 32 Articles of Christmas

- 2004: 31 Websites of Christmas

- 2003: 29 Issues of Christmas

- 2002: 28 Years of Christmas

- 2001: 33 Days of Christmas

- NINTENDO SWITCH ONLINE ARCHIVE

- REVIEW ARCHIVE

- FULL ARCHIVE

In the Beginning There Were No Reviews

While Game Player's may get the bulk of my scorn, there's still plenty of blame to go around!

It's not hard to find examples of this kind of practice. Perhaps the most well-known magazine guilty of this was none other than Game Player's, one of this industry's earliest video game periodicals. In the early days Game Player's (which would

Yeah, this pretty much sums up my experience with Total Recall on the NES!

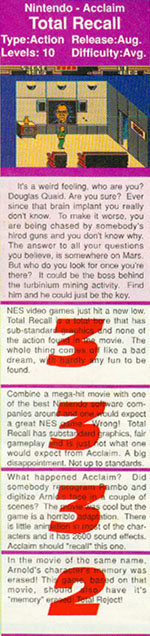

There's no need for you to take my word on it, this is how Game Player's magazine ended their Total Recall review in their September 1990 issue: "Total Recall, more than many other games based on movies or TV shows, offers a real taste of the story which inspired it. For anyone who has seen the film, it's familiar territory. For those who haven't, it's still an exciting and entertaining game."

Unlike Game Player's positive review, EGM opted to give their honest opinion!

The difference is obvious. Game Player's review (like most early reviews) pretty much said what the game companies PR wanted. It talks about the exciting action, crazy levels, and fact that fans of the movie will probably get a kick out of "reliving" the movie again. By contrast,

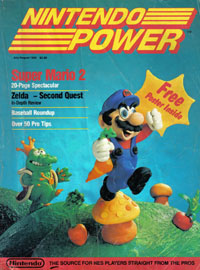

Ah yes, the days when Nintendo actually spent some extra time on their cover art!

But let's not spend too much time picking on Game Player's, they certainly weren't the only magazine writing non-review reviews. One of the more notorious examples of this is Nintendo Power, a magazine that was, above all else, about selling Nintendo games and systems. Nintendo Power is the closest thing the video game industry has to a state-run news network, and you could definitely see that when looking at their reviews. Like Game Player's, Nintendo Power was extremely positive about even the worst games, doing everything they could to convince their readers that they needed to buy each and every one of the games put out by Nintendo and their third parties.

Sorry Nintendo, but not only are games like Big Rigs bad, but they are fundamentally broken!

Now, keep in mind that not every magazine in the late 1980s was trying to pass off PR as an opinionated game review. The truth is, there were a number of publications that tried to have it both ways. One of those magazines was GamePro, the longest running multi-console magazine in the United States. It was clear from the start that, like Game's Players and Nintendo Power, GamePro wanted to offer up something similar to a review score, but

This is a sample review from GamePro, I don't advice you trying to read it (because it sucks and will hurt your eyes)!

To do this GamePro devised a scoring system that didn't score the actual game. That's right, they opted to score the graphics, sound, gameplay, fun factor and challenge, which gave them enough wiggle room to explain that the game is still fun, even if the "scores" at the bottom of the page were low. For years GamePro used these faces to indicate how good each of these sub-categories was, and then they replaced them ... with another set of faces. Eventually GamePro would finally man-up and give the games a real score, but not before redrawing those GamePro faces several more times.

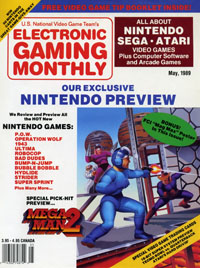

Even Electronic Gaming Monthly hesitated a bit when it came to reviewing games in their premiere issue. Instead issuing a number grade to each game, EGM originally used a

In this very first EGM issue the review crew actually reviewed games for the PC and Commodore 64!

In fact, in nearly every instance, when a game publication has moved from a scoreless review system to one with numbers, the game reviews seem to go from mostly positive to being a little more even handed. This is certainly true with Game Player's and Nintendo Power. These days Nintendo Power is ready and willing to give a bad game a low score, and the same was certainly true when Game Player's retrofitted their review section. Perhaps all it

This terrible scoring system was adopted by DailyRadar a decade later ... I'm not sure why!

Sadly, the need to kowtow to these game company's PR demands hurts a lot of early game publications. With no difference between a review and a preview, practically every page of these early game publications was the same. Some previews would have more pictures, there might have been a code section and most magazines featured a letters column, but by and large most game magazines were just repeating the PR line. It's hard not to feel sorry for the early games journalists, even if some of these wounds are self-inflicted.

By the early 1990s these non-review reviews were a thing of the past. With Electronic Gaming Monthly paving the way, magazines like Die Hard Game Fan and Video Games & Computer Entertainment followed suit. These days it's impossible to find a game review that isn't about that's writer's opinion, which is definitely a good thing. The world of 1988 was a confusing time I don't want to go back to; I would much rather live in a time when people aren't afraid to say what they really feel about a game.

HOME |

CONTACT |

NOW HIRING |

WHAT IS DEFUNCT GAMES? |

NINTENDO SWITCH ONLINE |

RETRO-BIT PUBLISHING

Retro-Bit |

Switch Planet |

The Halcyon Show |

Same Name, Different Game |

Dragnix |

Press the Buttons

Game Zone Online | Hardcore Gamer | The Dreamcast Junkyard | Video Game Blogger

Dr Strife | Games For Lunch | Mondo Cool Cast | Boxed Pixels | Sega CD Universe | Gaming Trend

Game Zone Online | Hardcore Gamer | The Dreamcast Junkyard | Video Game Blogger

Dr Strife | Games For Lunch | Mondo Cool Cast | Boxed Pixels | Sega CD Universe | Gaming Trend

Copyright © 2001-2025 Defunct Games

All rights reserved. All trademarks are properties of their respective owners.

All rights reserved. All trademarks are properties of their respective owners.