- CLASSIC MAGAZINES

- REVIEW CREW

A show recapping what critics thought back

when classic games first came out! - NEXT GENERATION'S BEST & WORST

From the worst 1-star reviews to the best

5-stars can offer, this is Next Generation! - NINTENDO POWER (ARCHIVE)

Experience a variety of shows looking at the

often baffling history of Nintendo Power! - MAGAZINE RETROSPECTIVE

We're looking at the absolutely true history of

some of the most iconic game magazines ever! - SUPER PLAY'S TOP 600

The longest and most ambitious Super NES

countdown on the internet! - THEY SAID WHAT?

Debunking predictions and gossip found

in classic video game magazines! - NEXT GENERATION UNCOVERED

Cyril is back in this spin-off series, featuring the

cover critic review the art of Next Generation! - HARDCORE GAMER MAGAZING (PDF ISSUES)

Download all 36 issues of Hardcore Gamer

Magazine and relive the fun in PDF form!

- REVIEW CREW

- ELECTRONIC GAMING MONTHLY

- ELECTRONIC GAMING MONTHLY RANKS

From Mario to Sonic to Street Fighter, EGM

ranks classic game franchises and consoles! - ELECTRONIC GAMING MONTHLY BEST & WORST

Counting down EGM’s best and worst reviews

going year by year, from 1989 – 2009! - ELECTRONIC GAMING BEST & WORST AWARDS

11-part video series chronicling the ups and

downs of EGM’s Best & Worst Awards!

- ELECTRONIC GAMING MONTHLY RANKS

- GAME HISTORY

- GAME OVER: STORY BREAKDOWNS

Long-running series breaking down game

stories and analyzing their endings! - A BRIEF HISTORY OF GAMING w/ [NAME HERE]

Real history presented in a fun and pithy

format from a variety of game historians! - THE BLACK SHEEP

A series looking back at the black sheep

entries in popular game franchises! - INSTANT EXPERT

Everything you could possibly want to know

about a wide variety of gaming topics! - FREEZE FRAME

When something familiar happens in the games

industry, we're there to take a picture! - I'VE GOT YOUR NUMBER

Learn real video game history through a series

of number-themed episodes, starting at zero! - GREAT MOMENTS IN BAD ACTING

A joyous celebration of some of gaming's

absolute worst voice acting!

- GAME OVER: STORY BREAKDOWNS

- POPULAR SHOWS

- DG NEWS w/ LORNE RISELEY

Newsman Lorne Riseley hosts a regular

series looking at the hottest gaming news! - REVIEW REWIND

Cyril replays a game he reviewed 10+ years

ago to see if he got it right or wrong! - ON-RUNNING FEUDS

Defunct Games' longest-running show, with

editorials, observations and other fun oddities! - DEFUNCT GAMES QUIZ (ARCHIVE)

From online quizzes to game shows, we're

putting your video game knowledge to the test!- QUIZ: ONLINE PASS

Take a weekly quiz to see how well you know

the news and current gaming events! - QUIZ: KNOW THE GAME

One-on-one quiz show where contestants

find out if they actually know classic games! - QUIZ: THE LEADERBOARD

Can you guess the game based on the classic

review? Find out with The Leaderboard!

- QUIZ: ONLINE PASS

- DEFUNCT GAMES VS.

Cyril and the Defunct Games staff isn't afraid

to choose their favorite games and more! - CYRIL READS WORLDS OF POWER

Defunct Games recreates classic game

novelizations through the audio book format!

- DG NEWS w/ LORNE RISELEY

- COMEDY

- GAME EXPECTANCY

How long will your favorite hero live? We crunch

the numbers in this series about dying! - VIDEO GAME ADVICE

Famous game characters answer real personal

advice questions with a humorous slant! - FAKE GAMES: GUERILLA SCRAPBOOK

A long-running series about fake games and

the people who love them (covers included)! - WORST GAME EVER

A contest that attempts to create the worst

video game ever made, complete with covers! - LEVEL 1 STORIES

Literature based on the first stages of some

of your favorite classic video games! - THE COVER CRITIC

One of Defunct Games' earliest shows, Cover

Critic digs up some of the worst box art ever! - COMMERCIAL BREAK

Take a trip through some of the best and

worst video game advertisements of all time! - COMIC BOOK MODS

You've never seen comics like this before.

A curious mix of rewritten video game comics!

- GAME EXPECTANCY

- SERIES ARCHIVE

- NINTENDO SWITCH ONLINE ARCHIVE

A regularly-updated list of every Nintendo

Switch Online release, plus links to review! - PLAYSTATION PLUS CLASSIC ARCHIVE

A comprehensive list of every PlayStation

Plus classic release, including links! - RETRO-BIT PUBLISHING ARCHIVE

A regularly-updated list of every Retro-Bit

game released! - REVIEW MARATHONS w/ ADAM WALLACE

Join critic Adam Wallace as he takes us on a

classic review marathon with different themes!- DEFUNCT GAMES GOLF CLUB

Adam Wallace takes to the links to slice his way

through 72 classic golf game reviews! - 007 IN PIXELS

Adam Wallace takes on the world's greatest spy

as he reviews 15 weeks of James Bond games! - A SALUTE TO VAMPIRES

Adam Wallace is sinking his teeth into a series

covering Castlevania, BloodRayne and more! - CAPCOM'S CURSE

Adam Wallace is celebrating 13 days of Halloween

with a line-up of Capcom's scariest games! - THE FALL OF SUPERMAN

Adam Wallace is a man of steel for playing

some of the absolute worst Superman games! - THE 31 GAMES OF HALLOWEEN

Adam Wallace spends every day of October afraid

as he reviews some of the scariest games ever! - 12 WEEKS OF STAR TREK

Adam Wallace boldly goes where no critic has

gone before in this Star Trek marathon!

- DEFUNCT GAMES GOLF CLUB

- DAYS OF CHRISTMAS (ARCHIVE)

Annual holiday series with themed-episodes

that date all the way back to 2001!- 2015: 30 Ridiculous Retro Rumors

- 2014: 29 Magazines of Christmas

- 2013: 29 Questionable Power-Ups of Christmas

- 2012: 34 Theme Songs of Christmas

- 2011: 32 Game Endings of Christmas

- 2010: 31 Bonus Levels of Christmas

- 2009: 30 Genres of Christmas

- 2008: 29 Controls of Christmas

- 2007: 34 Cliches of Christmas

- 2006: 33 Consoles of Christmas

- 2005: 32 Articles of Christmas

- 2004: 31 Websites of Christmas

- 2003: 29 Issues of Christmas

- 2002: 28 Years of Christmas

- 2001: 33 Days of Christmas

- NINTENDO SWITCH ONLINE ARCHIVE

- REVIEW ARCHIVE

- FULL ARCHIVE

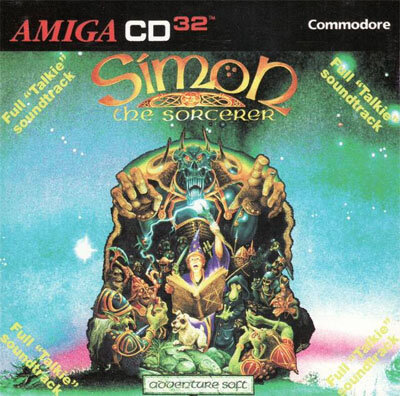

Simon the Sorcerer

Point-and-click aficionados looking for another adventure series like Monkey Island put their hopes in Simon the Sorcerer and those hopes were not misplaced. Simon has most of what made Monkey Island's Guybrush Threepwood a memorable and fun character to mouse-click across the screen; he is a young misplaced wanabee out of his element fully equipped with irreverent humor and a desire to prove himself amidst the sneers and jeers of doubtful townsfolk.

Just like several of C.S. Lewis' Narnia Chronicles, Simon the Sorcerer opens with an ennui-ridden, apathetic youngster with no deep purpose in his life who finds his destiny through a mythical dimension. Simon skulks around his attic to avoid doing homework, where his dog finds a magic book; being repulsed by more reading, Simon throws the book on the floor where it opens to reveal a transdimensional portal. His dog runs in, and Simon follows dutifully only to crash a party of hungry trolls. After escaping their cauldron, he learns his purpose: to confront and vanquish and evil sorcerer and save his new mentor Calypso (who we never actually meet in the game, sort of like Charlie from Charlie's Angels). With such a hackneyed plot, you may think Simon the Sorcerer has nothing special to give its player story-wise, but its dialogue, use of ridiculous props, and plethora of anachronisms make it anything but conventional. Simon's Groucho-esque duck-walk lets us immediately know that we are in for an adventure full of wisecracks.

Simon the Sorcerer for the Amiga CD32 is a basic port of earlier versions of the game with one vital difference: it talks. On its packaging, the Simon was advertised as a "talkie" and while this may give the game replay value for some who have already completed it, this feature could have easily been a bust for this already beloved game. Just as the transition from silent films to talkies was an awkward one, retrofitting computer games with voices came with mixed results. Flight of the Amazon Queen, for example, gave the lead character such a thick Brooklyn accent that he made William Bendix sound like an articulate orator. The voices in the highly acclaimed Beneath a Steel Sky were good and well-acted, but they loaded so slowly that many gamers disabled them and reverted back to reading text. With Simon the Sorcerer, however, the marriage is nearly perfect. Not only do the voices load quickly, but Simon's comic timing remains intact with the acting of the very capable Chris Barrie from the British sitcom, Red Dwarf. Most fans of British comedy will enjoy Barrie's stoic yet sarcastic delivery, which is, at times, on par with Rowan Atkinson's Blackadder character, who the game's head developer, Simon Woodruffe, has cited as an influence in the creation of the young wizard's personality.

From the start, we see the literary influences of this game-the Oxford Inklings, J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. Most of the references are overt and easily recognizable-Gandalf jokes, a convention-bound fanboy dressed like a Golem, a stone table with no purpose other than as a prop for Simon to refer about a lion being shaved and sacrificed. Impressively, the writers seem to give a subtle nod to Lewis' lesser-known work when Simon meets two demons named "Belchgrabbit" and "Snogfondle," names that seem like they can come directly from Lewis' Screwtape Letters with its own devilish minions with names like Toadpipe, Slubgob, Slumtrimpet, and the titular Screwtape. Most of the literary allusions are shameless and characters make several jokes about possible copyright infringement. Like Terry Pratchett's Discword novels and games, the parody that is Simon the Sorcerer was clearly written with a deep appreciation of fantasy fiction.

The game's failings are similar to those of most point-and-click adventures, namely pixel hunting. When in doubt, sweep your cursor across the entire screen until you hook onto a maneuverable object. Some objects are so camouflaged with the background that finding them verges on cruelty. While some adventures of this time came with tip-hotlines to unearth these, the game manual offers no such resource. Today, online walkthroughs are plentiful, but back in the day, many bleary-eyed gamers must have had a lovely time scanning their television screens for an owl feather or a book of matches.

Another flaw is the way this adventure ends. The long-awaited confrontation with the dark wizard Sordid is rather short and the whole thing ends without much fanfare. Many devoted adventurers have complained of this shortcoming, but the good news is that the ending hints at a sequel in a year's time, and sure enough it came two years later.

The idea of playing a point and click adventure on a home console hooked up to a TV may seem awkward or strange, but it sure beats having to swap floppy disks on a PC. This kind of games seem best suited for sitting at a desk with your mouse atop a flat surface, but it remains a strong title even for a system touted as a console rather than a computer. Too bad the system did not fare well long enough to see the release of Simon's sequel which many consider superior to the original.

(Note: If you play Simon on a NTSC system, you will need to use the joypad to access commands cut off at the bottom of the screen. Since the game was originally programmed for European televisions with a difference resolution, it does not stretch across U.S. televisions screens properly.)

Just like several of C.S. Lewis' Narnia Chronicles, Simon the Sorcerer opens with an ennui-ridden, apathetic youngster with no deep purpose in his life who finds his destiny through a mythical dimension. Simon skulks around his attic to avoid doing homework, where his dog finds a magic book; being repulsed by more reading, Simon throws the book on the floor where it opens to reveal a transdimensional portal. His dog runs in, and Simon follows dutifully only to crash a party of hungry trolls. After escaping their cauldron, he learns his purpose: to confront and vanquish and evil sorcerer and save his new mentor Calypso (who we never actually meet in the game, sort of like Charlie from Charlie's Angels). With such a hackneyed plot, you may think Simon the Sorcerer has nothing special to give its player story-wise, but its dialogue, use of ridiculous props, and plethora of anachronisms make it anything but conventional. Simon's Groucho-esque duck-walk lets us immediately know that we are in for an adventure full of wisecracks.

Simon the Sorcerer for the Amiga CD32 is a basic port of earlier versions of the game with one vital difference: it talks. On its packaging, the Simon was advertised as a "talkie" and while this may give the game replay value for some who have already completed it, this feature could have easily been a bust for this already beloved game. Just as the transition from silent films to talkies was an awkward one, retrofitting computer games with voices came with mixed results. Flight of the Amazon Queen, for example, gave the lead character such a thick Brooklyn accent that he made William Bendix sound like an articulate orator. The voices in the highly acclaimed Beneath a Steel Sky were good and well-acted, but they loaded so slowly that many gamers disabled them and reverted back to reading text. With Simon the Sorcerer, however, the marriage is nearly perfect. Not only do the voices load quickly, but Simon's comic timing remains intact with the acting of the very capable Chris Barrie from the British sitcom, Red Dwarf. Most fans of British comedy will enjoy Barrie's stoic yet sarcastic delivery, which is, at times, on par with Rowan Atkinson's Blackadder character, who the game's head developer, Simon Woodruffe, has cited as an influence in the creation of the young wizard's personality.

From the start, we see the literary influences of this game-the Oxford Inklings, J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. Most of the references are overt and easily recognizable-Gandalf jokes, a convention-bound fanboy dressed like a Golem, a stone table with no purpose other than as a prop for Simon to refer about a lion being shaved and sacrificed. Impressively, the writers seem to give a subtle nod to Lewis' lesser-known work when Simon meets two demons named "Belchgrabbit" and "Snogfondle," names that seem like they can come directly from Lewis' Screwtape Letters with its own devilish minions with names like Toadpipe, Slubgob, Slumtrimpet, and the titular Screwtape. Most of the literary allusions are shameless and characters make several jokes about possible copyright infringement. Like Terry Pratchett's Discword novels and games, the parody that is Simon the Sorcerer was clearly written with a deep appreciation of fantasy fiction.

The game's failings are similar to those of most point-and-click adventures, namely pixel hunting. When in doubt, sweep your cursor across the entire screen until you hook onto a maneuverable object. Some objects are so camouflaged with the background that finding them verges on cruelty. While some adventures of this time came with tip-hotlines to unearth these, the game manual offers no such resource. Today, online walkthroughs are plentiful, but back in the day, many bleary-eyed gamers must have had a lovely time scanning their television screens for an owl feather or a book of matches.

Another flaw is the way this adventure ends. The long-awaited confrontation with the dark wizard Sordid is rather short and the whole thing ends without much fanfare. Many devoted adventurers have complained of this shortcoming, but the good news is that the ending hints at a sequel in a year's time, and sure enough it came two years later.

The idea of playing a point and click adventure on a home console hooked up to a TV may seem awkward or strange, but it sure beats having to swap floppy disks on a PC. This kind of games seem best suited for sitting at a desk with your mouse atop a flat surface, but it remains a strong title even for a system touted as a console rather than a computer. Too bad the system did not fare well long enough to see the release of Simon's sequel which many consider superior to the original.

(Note: If you play Simon on a NTSC system, you will need to use the joypad to access commands cut off at the bottom of the screen. Since the game was originally programmed for European televisions with a difference resolution, it does not stretch across U.S. televisions screens properly.)

HOME |

CONTACT |

NOW HIRING |

WHAT IS DEFUNCT GAMES? |

NINTENDO SWITCH ONLINE |

RETRO-BIT PUBLISHING

Retro-Bit |

Switch Planet |

The Halcyon Show |

Same Name, Different Game |

Dragnix |

Press the Buttons

Game Zone Online | Hardcore Gamer | The Dreamcast Junkyard | Video Game Blogger

Dr Strife | Games For Lunch | Mondo Cool Cast | Boxed Pixels | Sega CD Universe | Gaming Trend

Game Zone Online | Hardcore Gamer | The Dreamcast Junkyard | Video Game Blogger

Dr Strife | Games For Lunch | Mondo Cool Cast | Boxed Pixels | Sega CD Universe | Gaming Trend

Copyright © 2001-2025 Defunct Games

All rights reserved. All trademarks are properties of their respective owners.

All rights reserved. All trademarks are properties of their respective owners.