- CLASSIC MAGAZINES

- REVIEW CREW

A show recapping what critics thought back

when classic games first came out! - NEXT GENERATION'S BEST & WORST

From the worst 1-star reviews to the best

5-stars can offer, this is Next Generation! - NINTENDO POWER (ARCHIVE)

Experience a variety of shows looking at the

often baffling history of Nintendo Power! - MAGAZINE RETROSPECTIVE

We're looking at the absolutely true history of

some of the most iconic game magazines ever! - SUPER PLAY'S TOP 600

The longest and most ambitious Super NES

countdown on the internet! - THEY SAID WHAT?

Debunking predictions and gossip found

in classic video game magazines! - NEXT GENERATION UNCOVERED

Cyril is back in this spin-off series, featuring the

cover critic review the art of Next Generation! - HARDCORE GAMER MAGAZING (PDF ISSUES)

Download all 36 issues of Hardcore Gamer

Magazine and relive the fun in PDF form!

- REVIEW CREW

- ELECTRONIC GAMING MONTHLY

- ELECTRONIC GAMING MONTHLY RANKS

From Mario to Sonic to Street Fighter, EGM

ranks classic game franchises and consoles! - ELECTRONIC GAMING MONTHLY BEST & WORST

Counting down EGM’s best and worst reviews

going year by year, from 1989 – 2009! - ELECTRONIC GAMING BEST & WORST AWARDS

11-part video series chronicling the ups and

downs of EGM’s Best & Worst Awards!

- ELECTRONIC GAMING MONTHLY RANKS

- GAME HISTORY

- GAME OVER: STORY BREAKDOWNS

Long-running series breaking down game

stories and analyzing their endings! - A BRIEF HISTORY OF GAMING w/ [NAME HERE]

Real history presented in a fun and pithy

format from a variety of game historians! - THE BLACK SHEEP

A series looking back at the black sheep

entries in popular game franchises! - INSTANT EXPERT

Everything you could possibly want to know

about a wide variety of gaming topics! - FREEZE FRAME

When something familiar happens in the games

industry, we're there to take a picture! - I'VE GOT YOUR NUMBER

Learn real video game history through a series

of number-themed episodes, starting at zero! - GREAT MOMENTS IN BAD ACTING

A joyous celebration of some of gaming's

absolute worst voice acting!

- GAME OVER: STORY BREAKDOWNS

- POPULAR SHOWS

- DG NEWS w/ LORNE RISELEY

Newsman Lorne Riseley hosts a regular

series looking at the hottest gaming news! - REVIEW REWIND

Cyril replays a game he reviewed 10+ years

ago to see if he got it right or wrong! - ON-RUNNING FEUDS

Defunct Games' longest-running show, with

editorials, observations and other fun oddities! - DEFUNCT GAMES QUIZ (ARCHIVE)

From online quizzes to game shows, we're

putting your video game knowledge to the test!- QUIZ: ONLINE PASS

Take a weekly quiz to see how well you know

the news and current gaming events! - QUIZ: KNOW THE GAME

One-on-one quiz show where contestants

find out if they actually know classic games! - QUIZ: THE LEADERBOARD

Can you guess the game based on the classic

review? Find out with The Leaderboard!

- QUIZ: ONLINE PASS

- DEFUNCT GAMES VS.

Cyril and the Defunct Games staff isn't afraid

to choose their favorite games and more! - CYRIL READS WORLDS OF POWER

Defunct Games recreates classic game

novelizations through the audio book format!

- DG NEWS w/ LORNE RISELEY

- COMEDY

- GAME EXPECTANCY

How long will your favorite hero live? We crunch

the numbers in this series about dying! - VIDEO GAME ADVICE

Famous game characters answer real personal

advice questions with a humorous slant! - FAKE GAMES: GUERILLA SCRAPBOOK

A long-running series about fake games and

the people who love them (covers included)! - WORST GAME EVER

A contest that attempts to create the worst

video game ever made, complete with covers! - LEVEL 1 STORIES

Literature based on the first stages of some

of your favorite classic video games! - THE COVER CRITIC

One of Defunct Games' earliest shows, Cover

Critic digs up some of the worst box art ever! - COMMERCIAL BREAK

Take a trip through some of the best and

worst video game advertisements of all time! - COMIC BOOK MODS

You've never seen comics like this before.

A curious mix of rewritten video game comics!

- GAME EXPECTANCY

- SERIES ARCHIVE

- NINTENDO SWITCH ONLINE ARCHIVE

A regularly-updated list of every Nintendo

Switch Online release, plus links to review! - PLAYSTATION PLUS CLASSIC ARCHIVE

A comprehensive list of every PlayStation

Plus classic release, including links! - RETRO-BIT PUBLISHING ARCHIVE

A regularly-updated list of every Retro-Bit

game released! - REVIEW MARATHONS w/ ADAM WALLACE

Join critic Adam Wallace as he takes us on a

classic review marathon with different themes!- DEFUNCT GAMES GOLF CLUB

Adam Wallace takes to the links to slice his way

through 72 classic golf game reviews! - 007 IN PIXELS

Adam Wallace takes on the world's greatest spy

as he reviews 15 weeks of James Bond games! - A SALUTE TO VAMPIRES

Adam Wallace is sinking his teeth into a series

covering Castlevania, BloodRayne and more! - CAPCOM'S CURSE

Adam Wallace is celebrating 13 days of Halloween

with a line-up of Capcom's scariest games! - THE FALL OF SUPERMAN

Adam Wallace is a man of steel for playing

some of the absolute worst Superman games! - THE 31 GAMES OF HALLOWEEN

Adam Wallace spends every day of October afraid

as he reviews some of the scariest games ever! - 12 WEEKS OF STAR TREK

Adam Wallace boldly goes where no critic has

gone before in this Star Trek marathon!

- DEFUNCT GAMES GOLF CLUB

- DAYS OF CHRISTMAS (ARCHIVE)

Annual holiday series with themed-episodes

that date all the way back to 2001!- 2015: 30 Ridiculous Retro Rumors

- 2014: 29 Magazines of Christmas

- 2013: 29 Questionable Power-Ups of Christmas

- 2012: 34 Theme Songs of Christmas

- 2011: 32 Game Endings of Christmas

- 2010: 31 Bonus Levels of Christmas

- 2009: 30 Genres of Christmas

- 2008: 29 Controls of Christmas

- 2007: 34 Cliches of Christmas

- 2006: 33 Consoles of Christmas

- 2005: 32 Articles of Christmas

- 2004: 31 Websites of Christmas

- 2003: 29 Issues of Christmas

- 2002: 28 Years of Christmas

- 2001: 33 Days of Christmas

- NINTENDO SWITCH ONLINE ARCHIVE

- REVIEW ARCHIVE

- FULL ARCHIVE

Beneath a Steel Sky

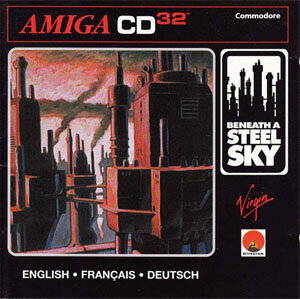

Today, old software is easily available via torrent hunts or easy-to-find downloads, yet Revolution Software's groundbreaking adventure game, Beneath a Steel Sky, is still in high demand in its original packaging. The box itself is a beautiful piece of commercial art: black with a silver stamped image of a futuristic cityscape hovering above the film-noir-esque title. But what makes this box so highly sought by collectors is what's inside: a short comic drawn by Dave Gibbons, the artist that had fleshed out Alan Moore's groundbreaking Watchmen series a decade earlier. In Gibbons deft hands, we are given the back-story of the game's protagonist, Robert Foster, the stranger stranded in a strange city-a jumble of metallic structures that starkly contrast against the Australian outback where he grew up among a tribe of hunters. Since the comic is the only exposition for our hero, it is not only valuable in terms of money, but also in helping us appreciate the full context of the story. (It should be noted that other versions of the game include longer intros with voiced-over digitized images from the comic).

Even if you don't own the original comic, you can still gander at Gibbons' artistry in the game itself. Just as his former work helped to bring the comic book medium into the realm of adult fiction, his bleak backgrounds in Steel Sky contribute in elevating what was once considered a children's pastime into a larger, more respectable form of entertainment. His hand drawn settings within Union City, like his dystopic New York in Watchmen, are washed in secondary colors helping to convey the dirtiness and grime of a future gone horribly wrong. Union City may sit beneath a steely blue-gray sky, but the city itself resembles rust. It is drained of color and makes a smoke-drab city like Pittsburg look like the iridescent Candyland. Today, when many players look back on Steel Sky, they remember it as much for its filthy, retro-futuristic look as they do for its better-than-average storyline. Luckily, its substance matches its style.

In Union City, we find our disoriented hero, a fugitive, Robert Foster, who, as a boy, survived a helicopter crash in the Australian Outback (now known as "the Gap"). From the Gibbons comic, we learn that he was rescued from the burning craft by an indigenous tribe who then accept them as one of their own. These natives name the boy "Foster"-a double entendre on both the Australian beer brand and the nature of the boy's fostered state. Years later, another helicopter lands and the crew abducts Foster before they lay waste to his adoptive family. This is where the game-proper begins, and appropriately we, the player, are as clueless its protagonist about our new surroundings. With the aid of his robotic sidekick, Joey-a droid who changes his host body every level or so-Foster's quest ultimately becomes a search for identity in a world where an overarching government has defined its citizens through a rigid class system of haves and have-nots. Without being preachy or pretentious, Steel Sky manages to play well while telling an engaging story about what happens when the infrastructure of an entire city reflects the egomania of only a privileged few.

Despite its grim look and serious subject matter, Steel Sky is not a downer. Foster's knack for sarcastic wit, understatement, and simile is like that of hardboiled detectives in old crime dramas. The mature but lighthearted tone is immediately apparent when Foster explores a mechanical press in a factory and makes the comment "It's whizzing and banging like an asthmatic dinosaur in the mating season." Later, Foster examines a random pipe in the city and remarks that "pipes are the arteries in this mighty erection." Such artful uses of figurative language are signs of a clear departure from more innocent games, and they somewhat prepare us for the more graphic instances that occur later (including brief moments of nudity and dismemberment). Sure, such is tame in our post-Grand Theft Auto society, but back in 1995, these moments may have been cause for double takes.

While Steel Sky may have more to say than other point-and-click adventures (nobody plays Monkey Island to study man's struggle for identity in post-colonial Caribbean nations), it falls short in creating mind-bending puzzles common to other games in the genre. There are a few Rube Goldberg solutions to some problems, but for the most part working out of a jam is a simple matter of finding the correct key card to use in a door. And of course, like most click-adventures, it has its share of pixel hunting (damn that invisible lump of putty in the storeroom!).

Perhaps the most satisfying and original bit of problem-solving comes via scenes that place Foster in a virtual world of Linc-Space (a virtual interpretation of a computer network). These screens are laid out like floating checkerboards laden with concrete renditions of abstract concepts in computer programming. For example, a magnifying glass is used as a data decryption tool and a knight in armor serves as program firewall. These cyber constructs are not unlike those one may find in a William Gibson novel and they help to legitimize Steel Sky as being truly "cyberpunk" even according to the strictest definition of that genre.

What sets the Amiga CD32 edition apart from the standard Amiga version are the voices.

Interestingly enough, the audio speech soundtrack does not always match the text on the screen. Many English terms are Americanized. For example, a "spanner" in text becomes a "wrench" in speech; "lift" becomes "elevator"; "smart" becomes "cool"; and "secateurs" becomes "shears". It is also strange that Revolution, a British development company, choose to give Foster, an Australian by birth, an American accent. Some reviewers overseas have found this casting choice insulting and see it as yet another example of how the American persona dominates in the creative psyche as the embodiment of heroism. Countless films with international casts place American actors in the savior role. (See: Star Wars, The Guns of Navarone, or most epic Biblical films). This complaint does have some merit, but the more likely reason for choosing an American voice was to imitate the sound of film-noir classics.

On the technical side of things, the voices do tend to load slowly, and quite often you can hear the console whirring and chugging to find the right voice track for each choice you make. While each delay isn't that long, they slow the game down as a whole. It wouldn't be surprising if many CD32 owners had disabled the voices in favor of good, old-fashioned text.

The overall enjoyment of Steel Sky also suffers from the resurrection fallacy (having to die before figuring out a solution) and this would not be a big deal if the game allowed for random saving. Rather, it is broken up into stages that reward a player with a code at the end of each level. But this and the game's other shortcomings do little to diminish its overall quality, and they probably won't stop you from wanting to persist and finish it.

Those who have yet to play Steel Sky are in luck as it has been LEGALLY available as freeware for several years. While there is no current plan for a sequel or update, its developer, Revolution Software, is currently refurbishing another of its fine titles, Broken Sword: The Shadow of the Templars (also with the aid of Gibbons) for possible release for the Nintendo Wii. In interviews, however, some folks at the company have hinted that if this succeeds, we may see Beneath a Steel Sky get its own facelift sometime soon. Here's hoping.

Even if you don't own the original comic, you can still gander at Gibbons' artistry in the game itself. Just as his former work helped to bring the comic book medium into the realm of adult fiction, his bleak backgrounds in Steel Sky contribute in elevating what was once considered a children's pastime into a larger, more respectable form of entertainment. His hand drawn settings within Union City, like his dystopic New York in Watchmen, are washed in secondary colors helping to convey the dirtiness and grime of a future gone horribly wrong. Union City may sit beneath a steely blue-gray sky, but the city itself resembles rust. It is drained of color and makes a smoke-drab city like Pittsburg look like the iridescent Candyland. Today, when many players look back on Steel Sky, they remember it as much for its filthy, retro-futuristic look as they do for its better-than-average storyline. Luckily, its substance matches its style.

In Union City, we find our disoriented hero, a fugitive, Robert Foster, who, as a boy, survived a helicopter crash in the Australian Outback (now known as "the Gap"). From the Gibbons comic, we learn that he was rescued from the burning craft by an indigenous tribe who then accept them as one of their own. These natives name the boy "Foster"-a double entendre on both the Australian beer brand and the nature of the boy's fostered state. Years later, another helicopter lands and the crew abducts Foster before they lay waste to his adoptive family. This is where the game-proper begins, and appropriately we, the player, are as clueless its protagonist about our new surroundings. With the aid of his robotic sidekick, Joey-a droid who changes his host body every level or so-Foster's quest ultimately becomes a search for identity in a world where an overarching government has defined its citizens through a rigid class system of haves and have-nots. Without being preachy or pretentious, Steel Sky manages to play well while telling an engaging story about what happens when the infrastructure of an entire city reflects the egomania of only a privileged few.

Despite its grim look and serious subject matter, Steel Sky is not a downer. Foster's knack for sarcastic wit, understatement, and simile is like that of hardboiled detectives in old crime dramas. The mature but lighthearted tone is immediately apparent when Foster explores a mechanical press in a factory and makes the comment "It's whizzing and banging like an asthmatic dinosaur in the mating season." Later, Foster examines a random pipe in the city and remarks that "pipes are the arteries in this mighty erection." Such artful uses of figurative language are signs of a clear departure from more innocent games, and they somewhat prepare us for the more graphic instances that occur later (including brief moments of nudity and dismemberment). Sure, such is tame in our post-Grand Theft Auto society, but back in 1995, these moments may have been cause for double takes.

While Steel Sky may have more to say than other point-and-click adventures (nobody plays Monkey Island to study man's struggle for identity in post-colonial Caribbean nations), it falls short in creating mind-bending puzzles common to other games in the genre. There are a few Rube Goldberg solutions to some problems, but for the most part working out of a jam is a simple matter of finding the correct key card to use in a door. And of course, like most click-adventures, it has its share of pixel hunting (damn that invisible lump of putty in the storeroom!).

Perhaps the most satisfying and original bit of problem-solving comes via scenes that place Foster in a virtual world of Linc-Space (a virtual interpretation of a computer network). These screens are laid out like floating checkerboards laden with concrete renditions of abstract concepts in computer programming. For example, a magnifying glass is used as a data decryption tool and a knight in armor serves as program firewall. These cyber constructs are not unlike those one may find in a William Gibson novel and they help to legitimize Steel Sky as being truly "cyberpunk" even according to the strictest definition of that genre.

What sets the Amiga CD32 edition apart from the standard Amiga version are the voices.

Interestingly enough, the audio speech soundtrack does not always match the text on the screen. Many English terms are Americanized. For example, a "spanner" in text becomes a "wrench" in speech; "lift" becomes "elevator"; "smart" becomes "cool"; and "secateurs" becomes "shears". It is also strange that Revolution, a British development company, choose to give Foster, an Australian by birth, an American accent. Some reviewers overseas have found this casting choice insulting and see it as yet another example of how the American persona dominates in the creative psyche as the embodiment of heroism. Countless films with international casts place American actors in the savior role. (See: Star Wars, The Guns of Navarone, or most epic Biblical films). This complaint does have some merit, but the more likely reason for choosing an American voice was to imitate the sound of film-noir classics.

On the technical side of things, the voices do tend to load slowly, and quite often you can hear the console whirring and chugging to find the right voice track for each choice you make. While each delay isn't that long, they slow the game down as a whole. It wouldn't be surprising if many CD32 owners had disabled the voices in favor of good, old-fashioned text.

The overall enjoyment of Steel Sky also suffers from the resurrection fallacy (having to die before figuring out a solution) and this would not be a big deal if the game allowed for random saving. Rather, it is broken up into stages that reward a player with a code at the end of each level. But this and the game's other shortcomings do little to diminish its overall quality, and they probably won't stop you from wanting to persist and finish it.

Those who have yet to play Steel Sky are in luck as it has been LEGALLY available as freeware for several years. While there is no current plan for a sequel or update, its developer, Revolution Software, is currently refurbishing another of its fine titles, Broken Sword: The Shadow of the Templars (also with the aid of Gibbons) for possible release for the Nintendo Wii. In interviews, however, some folks at the company have hinted that if this succeeds, we may see Beneath a Steel Sky get its own facelift sometime soon. Here's hoping.

HOME |

CONTACT |

NOW HIRING |

WHAT IS DEFUNCT GAMES? |

NINTENDO SWITCH ONLINE |

RETRO-BIT PUBLISHING

Retro-Bit |

Switch Planet |

The Halcyon Show |

Same Name, Different Game |

Dragnix |

Press the Buttons

Game Zone Online | Hardcore Gamer | The Dreamcast Junkyard | Video Game Blogger

Dr Strife | Games For Lunch | Mondo Cool Cast | Boxed Pixels | Sega CD Universe | Gaming Trend

Game Zone Online | Hardcore Gamer | The Dreamcast Junkyard | Video Game Blogger

Dr Strife | Games For Lunch | Mondo Cool Cast | Boxed Pixels | Sega CD Universe | Gaming Trend

Copyright © 2001-2025 Defunct Games

All rights reserved. All trademarks are properties of their respective owners.

All rights reserved. All trademarks are properties of their respective owners.